London Crawling

- Dan Synge

- Jul 24, 2025

- 4 min read

Updated: Jul 25, 2025

A new illustrated guide examines the glamorous and free spirited legacy of pre-war motoring. So how have we got stuck in the slow lane?

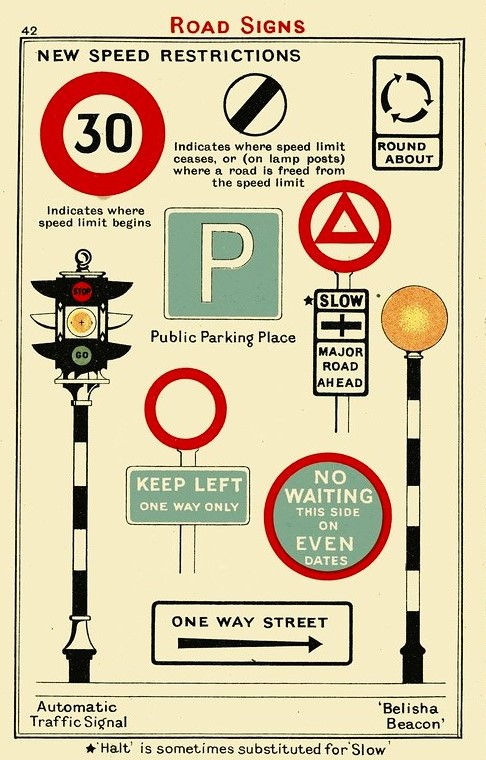

If, like me, you are one of the many thousands of motorists who have received a Notice of Intended Prosecution (NIP) from The Metropolitan Police’s Camera Processing Services, you’ll be surprised to know that under the 1930 Road Traffic Act (in which today’s Highway Code was first introduced) there wasn’t a mandatory speed limit for private vehicles. Of course, there existed a raft of regulations aimed at the most irresponsible and dangerous road users but no actual speed limit applied.

The reasoning behind this extraordinary piece of 20th century trivia was that, in those far off days, penalties for exceeding any speed limits were largely unworkable. After all, what use would the law be if no-one was there enforce it? Surveillance cameras were still decades away from being invented and most vehicles didn’t come equipped with a reliable speedometer.

These, and other bizarre facts from motoring’s golden age are found in the launch edition of Curious London alongside some splendid Art Deco garage forecourts and former industry headquarters such as the palatial Michelin House and The Wolseley Car Showroom, both of which are now popular high-end eateries. The inter-war period saw increased car usage in the capital and over two million private vehicles were registered the UK. Car-centric planners gave us the North Circular, Western Avenue and the Great West Road. And alongside them stood the iconic Hoover Building and the Firestone Factory, an Art Deco masterpiece which was sadly demolished in 1980. Golden age it may well have been, but clearly such a speed free-for-all was unsustainable. In the early 1930s, there were a shocking 7,000 road deaths annually peaking at almost 10,000 in 1941. Understandably a 30-mph ceiling for driving in built up areas became law following the subsequent 1935 Road Traffic Act. Indeed, thirty remained the urban standard until only recently when borough chiefs, aided and abetted by the Police, began to wage a more sustained war against the motorist. Now, it seems, we are all stuck with a funereal 20 mph. We are told this makes for a safer, greener and cleaner city and it helps to reduce fatal accidents. All well and good, but does that necessarily make our lives better?

In fact, city roads remain as hazardous as in those earlier, more carefree days of motoring. Not for hapless pedestrians, but for us saddos stuck behind the wheel who must now negotiate an impossible jungle of speed cameras, inconsistent road markings and the dreaded low traffic neighbourhoods (LTNs). While the rest of the economy seemingly lies dormant, at least our road signage manufacturers have been busy. Even as you stare dementedly at your speedometer, your poor brain computing every single imperative along the way, a costly misdemeanour is just around the corner. And all the time you sit stewing in the car you build more evidence of our dysfunctional transport infrastructure; the piles of upended Lime bikes on the pavement, balaclava-clad e-scooter warriors who cut across our bonnets at busy junctions, the freewheeling cyclist who decides that instead of using the new cycle lanes that TfL has provided for them, they will ride the pavement instead.

'We've lost our bottle, our joie de vivre and can no longer

make sensible decisions'

Driving around town could never be described as pleasurable, but even at a steady 30 mph the person behind the wheel feels some degree of control and perhaps even a sense of purpose and destiny. But at 20 mph or less, drivers are cowed into submission by the over regulation. We just can’t be trusted. And so in the process, we’ve lost our bottle, our joie de vivre and can no longer make sensible decisions for ourselves. Driving has become simply a case of avoiding the cynically installed traps or fiddling with apps like Waze to find out where they lie in wait. The stage is perfectly set for the new wave of self-driving vehicles which are expected to hit the road in 2027.

Meanwhile, the daily crawl endured by the increasingly anxious and uncertain is endemic of the fast-sinking national mood. Being regularly stuck below 20 mph is anti-risk, anti-growth and anti-ambition. Journeys that used to take minutes now take hours and, all the while, thirsty engines need replenishing. Not such the boost to the environment that our transport Tsars would have us believe. In the eyes of some of our European neighbours it makes us seem parochial and uncompetitive. Indeed, if setting off on an important car journey was an analogy for our country’s prospects, we are heading for a massive pile up. In his essay Politics and the English Language, George Orwell argued that lazy, cliché-ridden language led to an unwelcome vagueness and conformity in society. The kind of conformity which allowed Fascist and Communist doctrines to thrive during the era he wrote in, the 1930s and 1940s.

In response to the malaise, Orwell demanded a call to action, proposing rules for writers that included using active verbs only and cutting out long or unnecessary words in sentences. KISS (‘Keep it Short and Simple’) is the mantra of any aspiring journalist, even today. Oh, how our traffic laws and accompanying roadside architecture could do with such a shake-up! So instead of the terrible acronyms and the trust eroding petty criminalisation of law-abiding citizens – on their way to a busy job, taking a child to a music lesson or dropping a sick relative to hospital – how about getting this underperforming city to run that little bit more efficiently?

'Curious London,

Motoring in and around the city'

is out now

Comments